One in particular stands out among several unusual instructions given to new arrivals renting cars at Iceland’s Keflavik airport. ‘Please, always park your car facing the wind’, says the impeccably charming, smiling woman behind the desk, ‘never with your back to it’. Apparently, they have a significant problem with tourists who ignore this request, park any old how with the wind behind them, and then see their doors ripped off by the gale as they carelessly try to get out. OK, you say, that all sounds very thorough, maybe a bit excessive, but without thinking too much about it. It’s only when you walk out of the sleek glass box of the terminal building and first encounter the late-winter Icelandic wind that you fully realize what she’s been talking about. After a few minutes being buffeted around the parking lot looking for your vehicle it’s a real relief to get inside, perhaps with a mild feeling of concussion – and after, of course, taking due care in opening the doors. I understand that in midsummer, when daylight lasts 22 hours, the chill does tail off and temperatures nudge upwards into the high-teens Celsius, but few Icelanders seem willing to say that their winds can ever be relied upon to fall away completely. In February, as you drive around, you can be lured into thinking, ‘this looks a quiet spot, the wind must have dropped’. Hell no, as you find again as soon as you get out. It’s as permanent as the rocks.

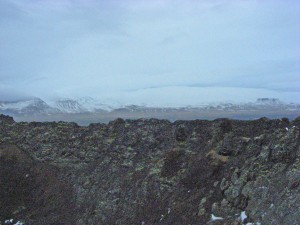

At first – or maybe second, or even third – sight Iceland can appear the most inhospitable place on earth. A lot of it looks no more suitable for habitation than the moon, beginning with the lava field of bizarre, gnarled rocks right outside the airport. So much so that the question soon flits across the brain of why anyone lives here at all. Things must have been really bad in Norway back in 874, you think, ever to make those Vikings think of settling here. It seems to have a whole lot more weather and geology than other, more ‘normal’ countries. Obviously, this is a nonsense, because everywhere has exactly the same amount of both, but in most countries – even tropical ones, most of the year – these can be incidental features that you can ignore if you so wish much of the time: a day can be just a nice day that makes a perfectly fine backdrop for anything you want to do, the structure of the landscape can be just something you look at in a walk before moving on to something else. In Iceland the weather throws itself at you in changing shapes all the time, from that wind to a constant stream of shifting skies, from iron grey to immense towering cloudscapes and then – maybe within the space of a few minutes – a magical, wonderfully translucent arctic blue, through which the sun gleams back dazzlingly off the ice and snow fields.

And the extraordinary geology is equally unavoidable, in relentlessly dramatic, lunar landscapes – glaciers, fjords, sulphur springs, empty lava fields, volcanoes both active and extinct, the natural thermal pools that Icelanders love to swim in. Volatile physical phenomena are everywhere. Even places with a bit more vegetation consist mostly of bare-blasted hills and valleys of coarse grass, in winter generally occupied only by little clusters of tiny, shaggy-haired Icelandic horses, standing in the wind like cartoon Eeyores with a look of invincible resignation.

Iceland’s mountains are not hugely tall, but there seems to be an endless succession of them, stretching away in magnificently gaunt rows. At Thingvellir, a valley of volcanic lakes and streams just 50 kilometres inland from Reykjavik that is a cradle of the Icelandic nation, site of the first parliament in the year 930, you can stand beneath a cliff that forms the Mid-Atlantic ridge, the easternmost point of the North American continental shelf, continually grinding against the European shelf on which you are standing (so that another unique feature of Iceland is that it is in both America and Europe).

To get Iceland and be drawn in by it, it’s fair to say, you have to connect with the fascination of being surrounded by this live, mobile natural world, the sheer spectacular strangeness of it all, a reminder of what’s beneath our feet elsewhere. And become a connoisseur of weather, as a major attraction. Otherwise, you miss the point.

Indoors, meanwhile, everything is warm, neat, snug, cosy and wood-panelled, impeccably heated by geothermal energy that comes (almost) straight out of the ground. If human beings ever succeed in colonizing other planets, they will resemble Iceland in winter: great expanses of hostile landscape between cocoons of well-equipped, well-insulated cosiness. Like any self-respecting space colony, highly-educated Iceland is already impressively high-tech: among the other things we’re enjoined to do by our car rental agent before setting off anywhere is to make at least daily checks on the amazing Icelandic weather (http://en.vedur.is/) and highways (http://www.vegagerdin.is/english/) websites, which forewarn you of changing conditions in every part of the country and on every single piece of road in fabulous and continually-updated detail (for Icelanders themselves, too, following the weather is clearly a major national pursuit).

Around two-thirds of Iceland’s 320,000 people, we’re told, live in the capital Reykjavik and its surrounding area. First impression on arrival is that this proportion must be much higher. Seen in passing Reykjavik looks like a dense knot of flash modernity somehow intruded into a sub-Arctic fjord, of lavishly glossy bank office blocks and shopping malls that look out of all proportion to a city of this size, the product of Iceland’s notorious intoxication with global finance prior to the great collapse of 2008. Very little of it looks more than 20 years old, and the crisis that followed the boom-and-crash seems to have been left behind already. Get beyond the Reykjavik peninsula, though, and a completely different scale of human habitation emerges. Long narrow roads wind around fjords and through fantastically empty valleys, with every so often tiny clusters of buildings visible in the distance, often around a church tower, dwarfed by the great flanks of mountainsides above them. In the global scale of human settlement, this is Lilliput. One aspect of Icelandic efficiency: even here, every hamlet, every farm, no matter how small, has its own very proper sign off the main road, so everywhere is very easy to find on the map.

In this country of isolated micro-settlements, here and there, often beside a fjord, there is a cluster that’s a little bit bigger, extending to larger buildings – fish factories, a lighthouse – and a few dozen houses, an Icelandic small town. These too have a remote, again eccentric, atmosphere all of their own. Some have a few stout, solidly Nordic 19th-century wooden buildings, relics of former whaling stations. They may be bigger than the micro-hamlets but they still make you wonder what it must be like actually to live here all year. There’s an air of the town in Twin Peaks, for anyone who remembers it; it’s pure conjecture, I know, but beneath the surface calm, dramas could run deep. This is the kind of place where not only must everyone know each other, they probably also know too much about each other. And on a winter day there’s generally not one person in the streets – apart from lost tourists – since everyone is presumably cooking up their dramas inside in windproof warmth. Except that in the early afternoon you’ll usually see at least one young parent, determinedly pushing a stroller with suitably well-swaddled tot along an otherwise deserted street. I’m convinced there must be a law making it obligatory for all new-borns to be taken out for some fresh air at least once a day whatever the weather.

The hubs of Icelandic small towns nowadays are their petrol/gas stations, essential modern national institutions. Most have at least two in competition, although oddly they tend to be next to each other. Together with their pumps they have attached at the very least a convenience store and café and snack counter; in Borgarnes, about 90 minutes north of Reykjavik, the N1 station also had a smart souvenir concession and a well-stocked bookshop. As well as a big grey car park, broad enough to allow ample blasting range to the afternoon’s gale. After battling with the wind to fill up you make your way inside, where everything is warm, bright, colourful and very new, a snug spot to hang out. Among other things they also have Iceland’s own variation on hot dogs – apparently introduced with the US Air Force when Keflavik was a NATO base during the Cold War, but which have become another national institution.

With their extremes of weather and geography, their contrasts of tight-knittedness and isolation, Icelanders could be expected to be a bit crazy, a bit cabin-fevery. And if you read any modern Icelandic crime novels, like those of Arnaldur Indridason, with their disfunctional characters, druggies and alcoholics, the impression is sustained, so probably some of them are. But, one can only report what one finds, and with a few exceptions most we met were disarmingly friendly and smiley, in a quiet way. And very well educated, something they may be a little smug about. Inland from Borgarnes is Reykholt, another tiny village of scattered, nothing-special houses in a wide, wind-blown, lost-world valley. Attached to the church is a fine exhibition centre, marking the fact that this was the home of Snorri Sturluson, the great patriarch of Icelandic literature, who at the end of the 12th century first committed the great Icelandic sagas to paper. And above this, as we were shown by the charming attendant – she had nothing else to do, there was no one else around – is an exquisite study library, dedicated to Icelandic and other medieval literature, with an extraordinary collection of early manuscripts. A certain kind of visiting scholar must be in ecstasy here, I think, huddled over priceless historic texts, with an occasional glance at the trees bent double in the wind outside, nothing else to hurry or disturb them, in a wonderfully comfortable, warm bubble with a feel of being a million miles from run of the mill concerns. An eccentric place.

Recent Comments