Deserts are giant sculptures. In the arid world stripped of normal fertility, moisture and softness, the comfortable shapes of more habitable landscapes give way to an extraordinary range of abstract forms and textures, stripped of any covering to make them more amenable to human touch. This is one of the things that give deserts their magnetic fascination.

Probably nowhere is this more so than in the Atacama desert of northern Chile. The contrasts and juxtapositions of rock and landscape formations are extreme: immense soft sand dunes alongside jagged lines of rock like the teeth of some malevolent earth monster, shimmering salt flats and salt mountains, windswept scrub plateaux and brown expanses of nothingness so featureless the moon – to judge from the bits the astronauts jumped about on – could seem a little cosy by comparison. And the Atacama sits at the bottom of the wall of peaks of the Andes, so that, bizarrely, everywhere in this most arid place on earth, should you wander off and get lost in the brown dust, you would be able to look up and be tantalised by the sight of massive snow-topped mountains, even in the hottest times of the year.

The Atacama is also a volatile and mobile place, where the physical world has a presence that you can’t disregard, and you are made acutely aware that it is in motion around you. Volcanoes are active, and geysers bubble up out of the ground. The salt mountains are still being twisted and turned by the pressure of the solid plates around them. Because of the minimal humidity the range of temperatures is extraordinary: from searing heat and extreme ultra-violet exposure in mid-afternoon, after midnight the temperature drops to around zero or well below. The temperature is never constant, so you might feel a sharp chill first thing in the morning, comfortable – but always changing – warmth for a while around midday, then be unable to sit for more than a few minutes in heat like a magnifying glass on the skin a few hours later before the temperature dips radically again as soon as the sun goes down. Even when you just walk into the shade you notice an immediate sharp change. In San Pedro de Atacama, the desert’s main tourist town, you’re just always putting on extra clothing or taking it off.

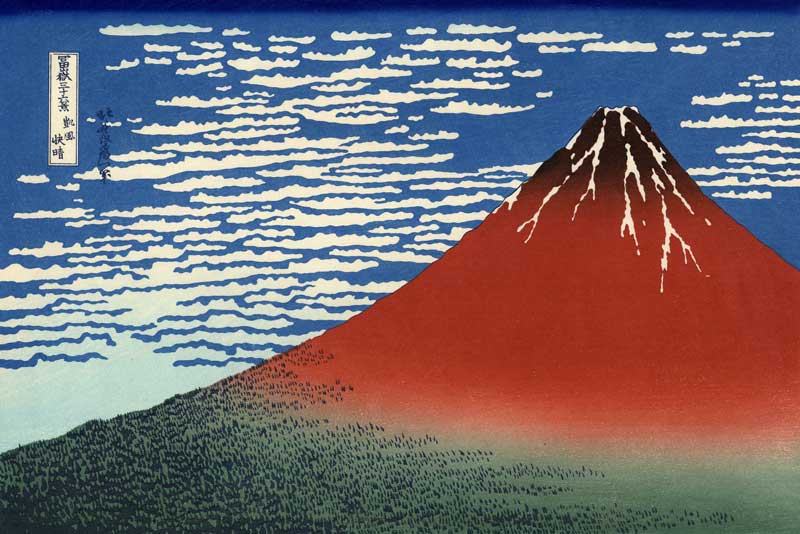

And this vast sculpture garden has immense, strange beauties. The Atacameños or Likan-Antay people, the desert’s indigenous inhabitants, apparently saw all their volcanoes as mighty giant-figures, who fought among themselves. And the majestic king of the volcanoes that preside over the Atacama, Mount Licancabur, is clearly a relative of Japan’s Mount Fuji:

In other parts of the Atacama, you can find crags and peaks with flowing, counterposed lines and masses that, had he ever made it to northern Chile, would surely have fascinated Cézanne even more than his usual mountains of Provence, and others that look vaguely Cubist. There is an endless range of colours, patterns and powerful forms, from abrasive to seductive, harshly aggressive to enticing.

Recent Comments