Why is the world so crazy about Antoni Gaudí? His architecture is Barcelona’s number-one identity-badge and calling card, even ahead of its football club, for Gaudí-mania seems to reach even those lost souls who still respond to the name Lionel Messi with blank looks. When I was back in the city a couple of weeks ago, on a supposedly off-season weekday, queues still trailed permanently around two sides of the block to get into the great heap of the Sagrada Família basilica – the most-visited monument in Spain, ahead of Madrid’s Prado with its Velázquez and Goyas and the glories of the Alhambra in Granada.

The attention cascaded over Gaudí often centres on just how weird his buildings are, how odd. Even freaky, as in all those who ever since the 60s have been coming out with ‘wow, just what was this guy on!’ (the very idea, unless you count rigorous fasting and penitential religious practices among narcotics). And maybe because of this it also centres on the Sagrada Família, since it is so plain huge and awe-inspiring. Seeing this as Gaudí’s essential masterwork, though, the real must-see, is now very questionable, since in the last 30 years it has gone well beyond what he actually created to become a bizarre hybrid all on its own, with a particular new brand of grotesque weirdness that can’t be attributed to the great man.

As is famous, when Gaudí was run over by a tram in 1926 only the three towers of the Nativity Facade and one part of the nave had been completed. Work theoretically went on to finish it, but for decades this didn’t seem to consist of much more than moving a pile of bricks every few months. All this has changed completely since the 1980s, as the banner of ‘it must be completed’ has been brandished with ever more fierce vigour by a strange, mysterious concatenation of international Gaudí-obsessives and ultra-conservative Catholics (and ‘mysterious’ here is not any kind of vague anti-Catholic slur: the basilica is being built by a private foundation, at arms’ length from the official Church, all donations are strictly secret, and its finances are notoriously opaque). At various times different voices from the architectural and artistic community have circulated appeals saying enough is enough, cannot Gaudí’s work be left alone, please, as an unfinished masterpiece, but this has only spurred bigger anonymous donations. Japan hosts a particularly intense Gaudí cult, and it is rumoured Japanese corporations have contributed millions of yen to the Sagrada Família. The Catholic Church itself long kept its distance, to avoid charges that this massive construction represents a colossal waste of resources, but the conservative Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI looked on it more favourably, culminating in its formal consecration with all the required pomp by Benedict in 2010.

The result is an accumulation of production-line new additions that are now larger than the parts actually built by Gaudí. It is true that Gaudí was obsessed by the Sagrada Família, especially in the last two decades of his life, and longed to see it finished, and also that the current builders always claim to be following his ideas. But whether he would have approved of the standard of what’s being done now is another thing; even at his strangest, he always had flair, and that’s something glaringly missing in the ‘new’ Sagrada Família. The drab statues of Etsuro Sotoo and Josep Maria Subirachs – like the kitsch Darth Vader-head figures supposedly representing Roman soldiers on the Glòria facade – have been surrounded by architecture of ever-increasing mediocrity. Among the latest touches are pinnacles topped by giant painted concrete fruit that look like an enormous juice stand.

And while, as said, the Sagrada Família was certainly the great obsession of Gaudí’s old age, its great bulk now masks the complex fascinations of the man. Foremost among them, what Robert Hughes called his ‘insatiable, self-critical inventiveness’, his inability to see a door, roof, air-shaft, seat-back or window-latch without redesigning them and making them in a completely new way, continually experimenting with new techniques and materials. This is the source of the dazzling intricacy of his buildings. And behind this is the great Gaudí paradox, the fact that all this torrent of innovation and fluid, searching creativity came from a man deeply out of step with the modern world, idealizing a medieval past and so devoted to an austerely puritanical, penitential Catholicism – throughout his life, but with ever-more intensity as he got older – that even other conservative Catholics found him intimidating and hard to follow. The full title of the Sagrada Família is that it is a Temple Expiatori, an Expiatory Temple, and what it was intended to ‘expiate’ was ‘the Sins of Modernity’, sins that it’s fair to say many of those now in the queues to see it have probably committed. In the mix binding together his inventiveness and religious intensity was a profound concern for craft, quality and attention to detail – something else spectacularly absent in the new sections of the Sagrada Família.

Other famous Gaudí sites, like the Parc Güell, allow you to appreciate his strange creativity far better, and one, the Casa Batlló apartment block, is shortly to launch a variant on the usual audio-guide tour that will give you a tablet, rather than the normal handset, which as you go through the house will show images of each room with its original furniture and fittings. Imaginative and well-conceived, it really expands on the experience of the visit. However, you still see these places in large numbers. It’s far rarer to see Gaudí without big crowds, and in a more domestic context.

Of the ten works by him in Barcelona, only two are private houses, and both are still privately owned. One, the Casa Vicens in the Gràcia district, is at least familiar from the outside, since its multi-coloured, vaguely Moorish-fantasy tiled exterior can easily be seen from the street, and its extravagant interiors have been frequently photographed. The other, the Torre Bellesguard on the flanks of the Serra de Collserola above Barcelona, has been the ‘unknown Gaudí’, closed off behind high walls and scarcely mentioned even in the umpteen books about the architect. For years, Gaudí enthusiasts who sought it out had to content themselves with trying to peek through the gates or jumping up and down to see over the exterior wall. However, since 18 September, in a complete change of approach, Bellesguard has been open to see, and keen to attract visitors.

To find Bellesguard you wander up the steep slope from Avinguda Tibidabo train station (at the bottom of the Tibidabo tram line). This area, Sant Gervasi, was virtually outside the city when the house was built in 1900–09, a favourite area for the wealthy of Barcelona to escape the heat in summer; today it’s one of its plusher residential districts, its tranquil streets lined with strikingly modern homes and smart private colleges as well as Modernista villas. The street on which the house stands – Carrer Bellesguard – swerves left around its massive stone perimeter wall, supported by a curious ‘viaduct’ of typically Gaudí Parc Güell-style tree-trunk columns, built after he realized that his extension of the Bellesguard garden would need a diversion of the existing track.

I was met at the gate by Pol Gago Guilera, a journalism student who’s one of the younger members of the Guilera family, whose house this is. They have owned it since 1945, when the great-grandfather of the current generation, Dr Lluís Guilera Molas, acquired it to use as a private medical clinic. An eminent cancer specialist, he was then barred from working in official hospitals because of his Catalanist and republican sympathies, and set up the clinic as a way to continue working, together with his son Dr Lluís Guilera Soler, an obstetrician. As a clinic, though, the house with its narrow staircases was ‘a nightmare’, and since the 1960s it has just been the family home. Currently 18 in total, over three generations, the Guileras are a very close-knit family; not all of them live there, but all of them use it, meet up there and are hugely attached to it. However, they never thought of opening it to paying visitors; Sra Amèlia, widow of Dr Guilera Soler and family matriarch, told me that her husband never wanted to ‘trade’ on the house, but didn’t mind leaving the gate open so that locals could use the garden. The panorama changed in 2009, when the controversial blasting-out by the city of a new water conduit nearby caused serious structural damage that required costly restoration. They realized they needed to do something with the house, or it might crumble away, or they might be forced to sell. The grandchildren took the initiative in finding ways of opening it up without losing the essence of the house, and inviting in experts to examine it. Reservations about letting the world in have been left behind, and Pol tells me they’re all excited by the new era. ‘In a way’, he says, ‘you rediscover your own house’.

Bellesguard has more historical associations than any other Gaudí construction. Archaeologists invited in since 2009 have discovered Roman remains dating back to at least the Second Century BC. Its foremost associations, though, are medieval. In 1408 King Martí “the Humane”, last of the line of native Catalan-speaking kings of Catalonia and Aragon, obese, chronically sick and rumoured to have tuberculosis, was told that for his health he should leave Barcelona and move to the hills. Supposedly a goat was cut into four pieces, which were scattered around Collserola, the great ridge that rises behind the city; the spot where it rotted the least, an ancient farm, was chosen as the place with the cleanest air, and so the site of the king’s new fortified manor house. The name, Bell Esquard, means “beautiful outlook”. While here he received news that his only son Martí the Younger, the hope of the dynasty, had died after a battle in Sardinia. Desperate for an heir, he married a beautiful young lady in waiting, Margarida de Prades, but to no avail, for he himself died within a year. With that, Catalonia’s own royal house came to an end, and the crown passed to the Castilian-speaking Trastámara dynasty. For romantic Catalan nationalists like Gaudí and his wealthy grain-merchant friend Jaume Figueras one could say that history had gone downhill ever since.

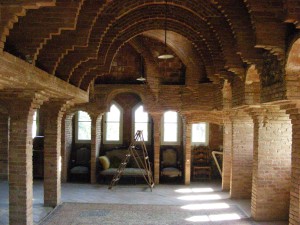

Both men were very aware of all these wistful associations when Figueras bought the ruins of the royal manor in 1900 and commissioned Gaudí to build him a summer retreat. If the Casa Vicens is his most Moorish-influence creation, Bellesguard is his greatest venture into medievalism, an intricate hymn to Catalonia’s first golden age. On top of the few remaining ruined walls he rebuilt bastions and battlements, a real mini-castle, all to enhance the views; dense banks of trees around shaded mosaic benches shield the house from the street. In the house itself, though, Gaudí naturally couldn’t just produce a neo-Gothic mansion like those that had sprouted all over Europe in the previous 50 years, but instead an exaggeratedly vertical dream-house topped by a tower with typical Gaudí four-sided cross, and faced with grey slate in multiple textures and colours that give the impression of something emerging out of the ground.

Bellesguard is also a great place to appreciate more closely the intricate intertwining of symbolism, metaphors and references to nature that Gaudí included in all his buildings. Though the house’s chief theme is that of a romantic evocation of medieval Catalonia, religious references are naturally here too; as Pol explains to me, the house and tower are 33 metres high, the traditional age of Christ at his death, the three balconies evoke God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, and the remarkable wrought iron main door combines what looks like a musical stave, ‘lacework’ in metal and an invocation to the Virgin Mary. Benches in Gaudí’s typical trencadís broken mosaic evoke incidents in Catalan history. Other elements are stranger, like the gorgeous eight-sided stained glass “Star of Venus” window in the main façade, potentially a symbol of fertility, Gaudí’s own interest in astronomy or even the Cathars, the medieval heretical sect who had been protected by the Catalan kings. Some of the benches show a cock and a hen, supposedly symbolizing Martí and Margarida. This maybe highlights another great Gaudí paradox: with his notoriously dour religiosity one doesn’t think of him as a ready man for a joke, let alone anything remotely off-colour, but so many of his ideas seem so playful, and it’s hard not to see this one as a perhaps unkind reference to the monarch’s desperate attempts at procreation.

As to the Casa Vicens, anyone who’s keen to see its celebrated interiors should know that it has theoretically been on sale for several years, through a website that tellingly is in English, Russian, Japanese, Chinese and Arabic. In the meantime the chances of ordinary interested visitors getting inside are effectively zero. There’s no confirmation of the asking price, but the word is that bids are not considered under 35–40 million euros.

The Bellesguard website is at http://www.torrebellesguard.cat/

Here also is an article I did on Bellesguard that appeared last week in the London Independent – http://www.independent.co.uk/travel/europe/grand-designs-with-gaudi-8822435.html

Recent Comments