Remember the End of the World? Three years ago, in December 2012, you couldn’t avoid it. Every media outlet in the world had at least some half-garbled report about how the ancient Mayans had some prophecy that their calendar would end on 21 December 2012, and that this would mean a global finale. The History and Discovery Channels went over to 24-hour apocalypse-vision, with this or that ‘expert’ murmuring darkly about just what form the cataclysm might take. Over a thousand books had appeared on 2012, and Net and Twitter traffic was beyond counting. Over 20 percent of China’s population and 12 percent of Americans were said to be expecting something dire on that day, and NASA felt obliged to issue denials that any such catastrophe was on the cards.

Which all suggests that this was something pretty important, a major global event. And then the day came, and went, and people stopped talking about it. The books are still there on Amazon, mostly heavily discounted. Many of the websites and Twitter feeds can still be found too, but no longer updated, gathering moss like the digital equivalent of Maya pyramids. Otherwise, silence.

Anniversaries of all kinds are marked these days, so now that three years have gone by it seems worth looking at 2012 again and considering quite what happened, whether anything or nothing. I was at one of the supposed epicentres of the whole event, the great Maya ruin of Chichén Itzá in the middle of Yucatán, on 21 December 2012. There was plenty of noise rather than silence, but it was still hard to pin down just what was happening to match the fuss. Why had they come and what did they expect from the day, I asked a variety of people. ‘Nothing, exactly,’ said Michael, from Connecticut, ‘I find when I start to expect things I’m only let down.’

A brief retread of the background: in 1966, in a sentence for which some of his colleagues have never forgiven him, the eminent Yale anthropologist Michael D. Coe wrote in his The Maya that ‘There is a suggestion’ that at the end of the thirteenth baktun of the Maya Long Count calendar ‘Armageddon would overtake the degenerate peoples of the world and all creation’. A baktun, around 400 years, is a central element in the Long Count, most intricate of the three calendar systems of the ancient Maya, and thirteen of them make up a Great Cycle, amounting to 5,125 years (so all known history fell within the then-current one). It was no wild idea to imagine that the Cycle-ending – which Coe initially calculated to 24 December 2011 before settling on 23 December 2012 – was a significant event to the Maya, but interpreting quite what it meant is hugely elusive, and few other Mayanists would have associated it so clearly with great transmutations or the biblical notion of Armageddon. In the 1970s all this was picked up by New Age authors like José Argüelles and Terence McKenna, who left aside the scholarly doubt of ‘there is a suggestion…’ to raise Maya beliefs to the status of ‘prophecies’, associate them with a grab-bag of similar visions, legends and traditions from around the world and suggest that the Cycle-ending would be the gateway to a new age of spiritual enlightenment and transformation, coinciding with a galactic alignment of sun and stars. They also shifted the date from Coe’s 23rd December to the 21st, the traditionally evocative date of the winter solstice.

Things only truly got going, though, with the emergence of the Internet, for 2012 was above all, categorically, a Net-driven phenomenon. Ideas that had lingered in esoteric bookshops began to be thrown around with fervour, and authors gained massive new print-runs. It is said that it was in 2007 that 2012-fascination reached critical mass on a global scale, but the arrival of Twitter gave vast new scope for the bubble to blow up even more. Overall 2012-ism came in two forms. One, shared by most of the New Age writers, was the image of the Great Cycle-ending and the start of a fresh cycle as the dawning of a new era for humanity, a cosmic rebirth. The one that really caught the media eye, however, and sparked most Twitter-traffic was the idea that the Maya saw the cycle-ending as a global apocalypse, doomsday. This reached a peak with Roland Emmerich’s spectacularly silly movie 2012, in which a spiral of catastrophes engulfs the world in a cataclysmic flood which a select few survive in giant arks, a neat use of the biblical to fill in all the gaps in Maya ‘prophecies’.

Net-powered 2012-ism had no real need for geographical roots, but even so it stayed stubbornly attached to the Maya, who provided it with exotic colour and a justification in ancient wisdom. Hence as the great date approached many felt the place to mark it had to be somewhere in the ancient Maya homelands. Some looked to Tikal in Guatemala, but far the most popular option was Chichén Itzá. This was in many ways an odd choice, for Chichén is a very atypical Maya city, and has far fewer Long Count date inscriptions than others further south. Its status had been boosted by 2012 writers such as John Major Jenkins, who theorized that its great Kukulcán pyramid predicted the cosmic movements leading to the galactic alignment. Plus, Chichén is by far the best known, best promoted Maya ruin, and the most easily accessible from major airports.

Archaeologists and other academically-based Mayanists looked on, some bemused, some irritated. Beyond the immense, untidy complexity of Maya beliefs in general, they pointed to inconveniences such as the fact that there are only two out of thousands of Maya inscriptions yet discovered that make specific reference to 2012 (neither with any clear prophetic meaning), or that there is no clear evidence of a link between Chichén Itzá and 2012. Astronomers pointed out that the galactic alignment is an imprecise event that had been underway since 1998.

Mexican authorities seemed pretty uninterested in the whole thing, until someone must have noticed just how much chatter there was in the rest of the world, and said they had to do something. Mexico City remained detached, but Yucatán State hurriedly put together a ‘Festival of Maya Culture’ to celebrate the baktun-end, with an amicable but disconnected relationship with all the New Age events (since 2013, with proper time to plan, this festival has taken on much more solid form, but has mutated into a wide-ranging general arts festival, and moved to October-November).

Thanks to the first festival, as part of an ‘official’ press trip, I was among the lines waiting to enter Chichén Itzá shortly after sunrise on 21 December 2012, when the site opened early to admit the expected crowds. It had been rumoured that over 200,000 were on their way, but actual numbers were far lower, only around 10,000 by day’s end. Serious New Agers were generally easy to identify among the otherwise curious and the world’s press waiting at the gates, since most were all in white. For those on organised tours this had been an instruction.

Once inside there was no tension or mass hysteria, but a lot of chanting, greeting the sun and the multi-eclectic ceremonies of the international, mostly North American, New Age. The larger and louder groups staked out spaces around the foot of the great pyramid. One of the loudest formed circles of white all chanting (in English, of course) with magnificently brash intensity –

I love you so… You help me see…

I see you in all, I see you in me,

I’m in you and you’re in me……

These were the followers of Fantuzzi, a musician turned guru/agitator/consciousness arouser who has been on a ‘Global Peace Tour’ at the intersect of the New Age and everything alternative quite genuinely ever since Woodstock. As well as a high-volume tenor voice for chant-leading he has a klieg-lamp charismatic smile, which I got full-on when he grabbed my hand with an avalanche-like ‘Hello, NICK!’. Was he particularly interested in the Maya, I asked. ‘We honour all the faiths, we honour all the paths’. Fantuzzi’s family was clearly the fun side of the New Age. As they looked rapturously into each other’s eyes, and chanted –

I wanna touch you, I wanna feel you, I wanna be by your side…

…it was easy to think some of them were soon going to go beyond the esoteric to the physical, right there on the grass.

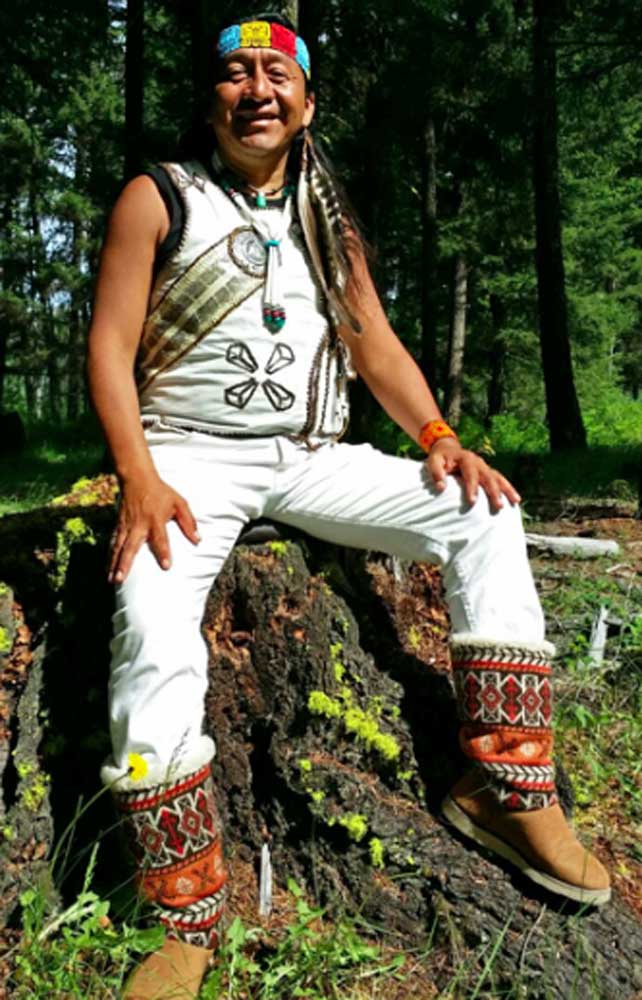

A short distance away lines of people in purple T-shirts were performing a kind of backwards calisthenics, led by a young guy who as he called out un – dos – tres – cuatro… up to ten kept getting the sequence mixed up and had to start again. These exercises, I was told, were to capture the energy of the pyramid, and would go on until the group would all head out of Chichén to repeat the same movements in reverse to transfer the energy to a new temporary pyramid built next to a restaurant in Pisté, the little town that’s the main service centre for the ruins. They were doing so on the instructions of another New Age ‘star’, Ac Tah, alias El Caminante Maya or ‘The Maya Walker’, a genuine local from Espita in the Yucatán cattle country north of Chichén who claims to have developed a new form of cosmic-geometrical knowledge based on the wisdom of his Maya ancestors. Local he is, but he dresses in a way never seen on any Maya villager, in tight white vest, white jeans, headband and feathered boots, like a Maya superhero, and also looks remarkably like Jackie Chan. ‘This is a geometry that we have worked on across the planet.’ he explained to me. ‘We are creating a new way of thinking… On the basis of movements we Maya create neuronal networks that allow us to understand and create new consciousness and a new reality’.

Much larger-scale activity was associated with Synthesis 2012, an all-in festival of ceremonies, workshops, meditation sessions and – outside in Pisté – camp grounds and music stages which often appeared to be marketed as if it ‘owned’ December 2012 at Chichén. Its prime mover was Michael DiMartino, a veteran of the US alternative festival scene. Denounced by one former collaborator as a ‘delusional megalomaniac’, he would fast become a hate object for participants and ticket-holders (some of whom had paid $500 a head) as they complained of campsites and transport unprovided, bills unpaid and other failures, and since early 2013 he seems to have gone to ground completely, pursued by lawyers and the contributors to the ‘Synthesis2012 Scam Awareness’ Facebook page. On the 21st, though, DiMartino was far more mellow. Looking like a mix of golden-haired Jesus and permatanned surfer god, he said the festival was ‘amazing… so many amazing teachers and masters sharing everything from the most ancient knowledge to futurists and scientists and visionary thinkers… An awesome opportunity’.

Around the signed-up groups wandered a larger number with no clear affiliation and differing degrees of commitment. Mariah, a quietly serious African-American woman from St Louis, said that she had come to ‘celebrate the New Age’, and hoped she would ‘feel the change’ at the solstice hour, though without too much concern if she didn’t. Kristoph, a young man of South Asian extraction who spoke English with a precise Scandinavian accent, was wearing a kind-of Asian robe and carrying a giant lily. When I asked a standard boring-journalist question (‘where are you from?’), and he answered ‘I’m from the Universe’, I initially took this as New Age rhetoric, but it turned out to be a fairly straight description of his personal situation: ‘We must come to a definition of where one is from’, he went on, ‘I was born in one place but of different nationalities, so I don’t understand what it means to be from somewhere’. He’d been thinking of coming to Chichén Itzá for 2012 for a long time, but was still vague on what he hoped for from the day: ‘I suppose I expect nothing,… I expect myself to create something beautiful out of it.’

Raúl and Laura from Guadalajara were impressively knowledgeable about Maya culture, and grumbled at how little the New Age ceremonies had to do with anything Maya. Matt and Rebecca from New York had decided to come that same morning when they’d seen it was cloudy in Cancún and not a good day for the beach. And a 92-year-old retired doctor from Tennessee told me he’d wanted to see Chichén Itzá all his life, and the fact that he arrived there amid the show on December 21 2012, brought by his grandchildren, was pure coincidence.

Some around the pyramids showed a certain dour religious ardour, but the overwhelming atmosphere was of people enjoying the day. New Agers came together in their rituals as they could have done in any other cool spot in the world, and even in the most apparently intense meditation circle someone would crack up and giggle if you took their picture. At a time when religion is so often an excuse for vicious hatred there was a likeable lack of sectarian, judgemental intensity.

What was emphatically not present at Chichén Itzá on 21 December was the global apocalypse, or any visible believers in it. All kinds of rumours had been going around about mad doomsday cults, said to have been converging on Chichén to commit mass suicide, mass murder or both, which had got the local authorities seriously worried. So much so that in mid-morning they provided extra protection… from Yucatán’s girl and boy scouts, neatly-uniformed kids who stationed themselves around all the major monuments. It’s hard to think how they would have handled any determined death-cult, but this was OK, as they were never tested. The optimistic dawn-of-a-new-age believers may have been fewer than promised, but they did at least turn up, whereas the supposed global doomsday-prophets were thankfully nowhere to be seen. A well-heeled Chinese couple said they’d been told the sky would go dark for three days, but laughed when they said it, like most people not taking it seriously.

So the Maya Apocalypse, like so many things, was really only available online. The 2012 topic that had most captivated the mainstream media, generated the most cyber-traffic, inspired a Hollywood movie and hours of crap TV and (we were told) got Ashton Kutcher, George Lucas and several others really worried, turned out to be… What? Just puff, nothing to do with the Maya and nothing anyone was willing to spend on an air ticket for, nor even get off the sofa. Just one more way of prodding jaded sensibilities to pass the time (everyone enjoys a good catastrophe), like the dumb babble that fills up so much of the Twittersphere.

One thing did stick out among the people I talked to at Chichén: scarcely any – and only Mexicans, none of the foreigners – knew much about the Maya. The transformation in knowledge of the ancient (and still very much existing) Maya since the 1960s has been one of the greatest intellectual adventures of modern times. First Maya glyph writing, never previously understood, was deciphered, and since then thousands of inscriptions have been painstakingly interpreted, once-neglected sites have been excavated, and what we know about Maya beliefs, farming, warfare, art, trade, politics has mushroomed. And it’s still going on, and major discoveries are still being made: a whole, large, previously unknown Maya city – Chactún – was revealed in southeast Yucatán only in June 2013. The result is a picture of enormous complexity, a developing work in progress. New finds throw up new insights, and old ideas have to be continually questioned and argued over.

None of the New Agers I spoke to on 21 December seemed to have read any of this stuff, nor showed any interest in it, even those who’d read a string of New Age titles supposedly on the same subject. Complexity and doubt in themselves seem to be a problem: the approach of ‘academic’ Mayanists is questing, tentative, uncertainty is essential to the fascination – as Dan Griffin, a Mérida-based researcher said to me, ‘Every archaeologist I’ve met will never state something unless they have ten different ways to prove it’. New Age writers in contrast take maybe one or two commonly known things about the Maya – like bits of the calendar – and go straight on to provide a new set of cut-and-dried, fully-formed, pre-packaged certainties, often with a dose of messianic personal grandstanding (I, working alone, have discovered…) that would make the most egotistical archaeology professor blush.

The Maya – and all native American peoples – have repeatedly been the butt of other people’s fantasies, right back to when Columbus linked his discoveries to prophecies of the Second Coming of Christ. And then, in all the 2012-chat, the Maya were on the one hand sufficiently weird, little-known and simultaneously unthreatening to be set up as a mass joke, a target for mass hysteria or malevolent racist abuse of the ‘FUCKING STUPID MAYANS!!! You say world’s gonna end! WE AIN’T GOING NOWHERE!!!’ kind that ran through #Mayans and other threads on Twitter. On the other, while the New Age believers in the calendar-end as ‘transformation of consciousness’ were at least smiley and good natured, even they were interested in the Maya only as a peg on which to hang their own beliefs.

As for the living, modern Maya, beyond a few incorporated into the New Age like Ac Tah, they had only walk-on parts in 2012. A guide told me that the site wardens at Chichén had been offended that the New Age cults had begun their multi-flavoured ceremonies without first asking the permission of the aluxes. Not many modern village Maya know much about the Long Count calendar, but everyone knows about aluxes, mischievous, leprechaun-like earth spirits, (some say) the ghosts of pre-Conquest gods, and pay their respects to them to get them onside before working a new piece of land, or before starting work at Chichén Itzá every day. There were also the handicraft sellers from nearby villages who normally flock around the Chichén site, who, however, had been told they all had to leave by 3pm to make way for the expected international crowds and their rituals. I asked Señora Ligía, from Pisté, what she thought of the baktun-ending. ‘People expect big things’, she pondered, ‘…But life now is something else. We work here, we come here to work every day’.

Recent Comments